|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

Madness At The Edge Of Science What is it that we love about the mad scientists in our movies and history? Is it because their probing of the unknown piques our curiosity? Is it their seeming superiority to the common herd? Or is it that they -- at least for a while -- get away with more than we can? They do so in many realms of knowledge. Some of them are practical, and quest for better things for the human race. Others are decidedly less practical. One of their most prominent technologies has been advanced medicine. Filmic mad scientists of the 1930s and 1940s led the vanguard in such efforts as keeping organs alive outside the body, cryogenics, new methods of surgery, robotic parts for humans, and new serums. Others harnessed electricity for all sorts of uses, but mostly to bring dead flesh back to life (always a useful ability), or to power advanced robots and death rays. In fact, their films have been hotbeds of fortean technology, introducing then-taboo ideas, preparing audiences for technological development in a world in which moral and scientific values would change and old taboos would be discarded. The movies render such taboo topics psychologically "safe" by making the inventions those of "madmen." The scientists who have uncovered the great secrets and developed the miraculous inventions in real life have been a decidedly less colorful lot -- if one disallows such exceptions as Nikola Tesla, Jack Parsons, Wilhelm Reich, Timothy Leary, John Lilly, Sir Fred Hoyle and Prof. Kevin Warwick. Most of the "boffins" who helped develop the atomic bomb and other such wonders were reportedly all too normal. But their proclivities for blithe destruction have often left their cinematic versions far behind. It is the potential for cutting-edge science to wound that makes fictions about the subject relevant. In the movies, scientists are quite often "mad," and have been so since the silent movies. The things they do, however, have been fairly consistent. They tend to be smarter than the heroes, and have wittier lines, often of a boastful nature. A surprising number can play Bach's Toccata and Fugue from memory. They will persevere despite repeated failures. These are usually on human subjects whose remnants, living or dead, are stored in commodious basements. Often unreliable technical equipment, anatomical parts and/or lab assistants plague the scientists. None of their electrical devices have fuses, though their machines tend to come equipped with overload switches to make sure their laboratories can explode during the last reel. These people are enthusiastic about their work, perhaps even carried away with it. They will let no one get in their way, especially those who call them insane, and start -- but do not finish -- going for the authorities. Generally their creations, be they mechanical or living, go out of control. Until the climax, that is, when they turn on their creator(s) and are soon destroyed themselves. This is usually due to fate, or "God," which restores the status quo against the blaspheming mad scientist. And it is this last motif that connects the various aspects of the subject together: the "god-like" man who rejects the accepted ways and pursues the unknown, running into trouble as a result. Alchemical Precursors An early prototype for the movie mad scientist is the alchemist. Considered by chemists to merely be their primitive precursor, the true alchemists of the Middle Ages were actually, it appears, pursuing a spiritual development technique in which spirit, symbol and physical manifestations were yoked together. Alchemical work is sometimes reflected in the well-known stereotype of the mad scientist, one of the most famous motifs of which is the artificial creation of life. Paracelsus (circa 1493-1541), perhaps the most famous alchemist, claimed to know the secret of creating a "homunculus" (a tiny artificial man) by means of a complex process whose first step was the burying of sperm -- within a sealed glass container -- in horse dung.1 One alchemist who may have influenced the literature of mad science was Johann Konrad Dippel (1673-1734). A man of great pride, he felt no limitations to his intellect and was interested in pursuing the great mysteries. When he registered at the University of Giessen (sixty miles north of the real Castle Frankenstein near Darmstadt, Germany), he registered as "Franckensteina." Some three years later he completed his dissertation. As it was a skeptical work -- whose title De Nihilo meant "On Nothing" -- it outraged many of his superiors.2 Dippel is remembered these days for a few achievements. He was the formulator of Dippel's oil, a nerve stimulant and anti-spasmodic once widely used. The discovery of the chemical -- potassium ferrocyanide -- used in the artists' pigment Prussian blue was his. Dippel was a pioneer in psychosomatic medicine as well. He was apparently more interested in other things. These included acquiring riches through "alchemy," involvement in political intrigues, and studies on the mechanisms of life. Like the fictional character Dr. Frankenstein, he was an ardent vivisectionist, had ideas on how to restore life to the dead, and he was reportedly interested in performing his many secret researches in Castle Frankenstein -- though his death ended his attempts to secure the place. Dippel's life, like that of many of his sort (the Comte de Saint Germain, for example) was a mixture of genius and deceit, in the interest of goals we can only guess at.3 |

|

|

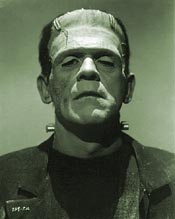

Frankenstein's monster (Boris Karloff) as seen in Frankenstein. ©1931 Universal Pictures.

The injured monster as he appears in The Bride of Frankenstein. ©1935 Universal Pictures.

|

|

Frankenstein Dippel's "alter ego," Victor Frankenstein (the fictional creation of Mary Shelley), has, through movies on the creation of artificial life, become the arch "mad scientist." We will here be concerned with his various movie incarnations. While there were two, minor silent film versions of the Frankenstein story, the classic Universal Studios version of 1931, with Boris Karloff as the monster, became the touchstone for all that followed. Its scientist, renamed Henry Frankenstein, works in an old watchtower strongly resembling the tower used in the 1926 silent film The Magician, which featured alchemical elements. Dr. Frankenstein, though not perhaps certifiably mad, is near that point in his obsession about creating new life from stitched-together corpse parts -- if "madness" if being obsessed with something people think is impossible. He keeps his uncanny creation locked away. It, after the fashion of most monsters, manages to escape and terrorize the countryside. During a siege by a torch-bearing mob, the doctor is carried off by the monster and, after a confrontation with it in an old mill, is nearly killed. In reference to his progenitors, Frankenstein had the same sort of relationship with his superiors at the University he attended as did Dippel. As performed by Colin Clive, he was as intense about his obsessions as any "mad" doc that followed. The sequel, The Bride of Frankenstein (1935), stresses the alchemical influences more strongly. A prototypical alchemist, one Dr. Septimus Pretorius, blackmails Dr. Frankenstein into creating a woman. Dr. Pretorius has earlier succeeded in creating a collection of homunculi, but is unable to make a normal-sized being, so is inspired to collaborate. While the brain for the female monster is created alchemically by Pretorius, its other parts are, like those of its intended husband, second-hand. Like Frankenstein (and Dippel), Pretorius was a controversial presence at the University and, as he relates to Baron Henry Frankenstein, "was booted out, booted, my dear Baron, is the word, for knowing too much." The Bride of Frankenstein, amusingly, was one of the earlier films to equip its mad lab with an all-purpose, self-destruct switch. Sons Of Frankenstein The third film in the series, Son of Frankenstein, was made in 1939. The finished film abandons most of the alchemical elements in favor of superscience, but an earlier October 1938 draft of the screenplay has a very interesting reference. Wolf von Frankenstein, the son of Henry, has inherited Castle Frankenstein, which he has not seen since childhood. Visiting its library, he reads off a familiar shelf of his father's books, soon quoting from memory: "Agricola's De Re Metallica ... the Necronomicon ... Roger Bacon ... Euclid ... Paracelsus ... FitzJames O'Brien ... Avicenna! See -- I haven't forgotten!"4 Not only was scriptwriter Willis Cooper (the original scriptwriter of the Lights Out radio show) aware of the alchemical precursors, but was acquainted with H. P. Lovecraft's Cthulhu mythos as well. In the completed film, Basil Rathbone plays a normal, if highly strung, scientist who, step by step, is made "mad." Upon inheriting the Frankenstein estate, he and his family move there, with no intention of carrying out his father's "unholy" work. Yet the authorities and the villagers of Frankenstein suspect he will carry out researches like those of his father. When Wolf discovers that the monster still survives in a coma, tended by Ygor, he revives the monster, under controlled conditions, hoping to vindicate his father. Needless to say, he gets carried away when he does so, and things go awry. Soon he is alienating nearly everybody, and only when he destroys his father's reanimated creation is he restored to the good graces of the community. Son of Frankenstein hews, as did its two predecessors, to the usual conventions. |

|

Peter Cushing has heart as Dr. Frankenstein in Evil of Frankenstein. ©1964 Universal Studios. |

|

While there were further Frankenstein sequels put out by Universal Pictures, all of them equipped with colorful mad scientists of one sort or another, it is probably more productive to move on to the remakes of the story released during the '50s and thereafter, for the best of them crystallized some themes implicit in their forebears. The first of these, Hammer Film Productions' The Curse of Frankenstein (1957), created a more rebellious doctor than the Universal films dared, because there was a more relaxed censorship standard at that time. The doctor is no longer depicted as sympathetic; in fact the interest of the film is directed towards the scientist rather than the monster. Peter Cushing's doctor is not "mad" in the same way, being ever so cool and collected as he carries out his scientific heresies -- in addition to a few casual murders when needed. In this film, he has no moral compunctions at all. But as the Hammer series progressed, Peter Cushing's character became increasingly honorable up to and including the fourth picture. This trend caused one critic to refer to the role as "Bishop Frankenstein." However, his increased ethics did not improve the successes of his creations, which were still faulty -- to put it mildly. The most recent remake of the original tale, the 1994 Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, features a slightly sensual monster-creation scene (the movie's star and director, Kenneth Branagh, works shirtless in the scene) but misplaces its monster (Robert De Niro) amidst chaotic camera movement. What could have been the greatest Frankenstein film of all thus misfires. Playing God In the foregoing pictures, there is one overriding theme: that man is taking too much upon himself when he decides to play God, for which he does not have the ability. Thus the parodies of humanity he creates act as rebukes to his hubris. They are to him as he is to God and hint that the faults in the human situation may relate to an equally flawed supreme being who would allow such pain and degradation to exist. This philosophy is at odds with Darwinian theories of the gradual improvement of species by survival of only the fittest. From this springs the dark humor that punctuates the Frankenstein films. In fact, the mad scientist motif nearly always hints at an incipient anarchy that could dominate everything if not stopped. It is not that the mad scientists' aims in themselves are evil; sometimes they are positive. But they threaten to change the world, which is either a good or a bad thing depending on your point of view. When brilliant people go beyond the "permitted" limits into new and uncertain endeavors ("blasphemies," "frauds," or "insanities" to those who do not want to understand them), others often get worried and try to put a stop to them. Real-life examples include the FDA burning of Wilhelm Reich's books and notes, the jailing of Timothy Leary, and the work of organizations like CSICOP which oppose "paranormal" researches and pursuits. |

|

Fredric March and Miriam Hopkins in Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. ©1932 Paramount Pictures.

Spencer Tracy's dark side as Mr. Hyde in the MGM version of the classic tale. ©1941 MGM. |

|

Dr. Jekyll: The Monster Within Returning from real-life "madness" to "reel-life," it is rewarding to survey some of the fictional mad scientists of the movies. Perhaps the most well known of all is the eminent Dr. Jekyll, famous, like others who could be mentioned, for his drug problem. Unlike Frankenstein, Dr. Jekyll's step beyond bounds is to create a monster from within himself. John Lilly, in the nonfictional book The Scientist, describes incidents involving the drug Ketamine (situations reminiscent also of the movie Altered States) in which dangerous, primitive, primate psychological "programs" were activated by drugs that may have been handled without enough care.5 A recent movie version of the Robert Louis Stevenson story The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde was entitled Mary Reilly and it tells the tale from the point of view of Dr. Jekyll's housemaid. Unfortunately, the normally superb John Malkovich does not separate the natures of Jekyll and Hyde enough and some of the dramatic values are lost. The much-filmed Dr. Jekyll is but one of many such early "leading-edge" scientists. Lon Chaney Sr., in the silent picture A Blind Bargain (1922), portrays both a scientist, who performs animal gland transplants on humans, and one of his resultant beast-man creations. Rudolph Kleine Rogge, as the outrageous scientist Rotwang, creates the first of an intended race of robot workers in Fritz Lang's classic science-fictioner Metropolis (1926). He wears a black glove over a crippled hand (a motif later used in both Son of Frankenstein and Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb). Invisible Insanity The best mad scientists of the following decade were Dr. Griffin and Dr. Moreau. Claude Rains, in The Invisible Man (1933), played the former. When we first meet Jack Griffin, he is already the victim of his own experiments: invisible and wanting an antidote. Unlike the H. G. Wells book upon which the movie is based, his descent into megalomania is an overlooked side effect of monocaine, the drug he has used to make himself unseen. An extra emphasis on megalomania is borrowed from a Wells-inspired novel, written by Philip Wylie, entitled The Murderer Invisible,6 which further elaborates on the concept of an invisible man wanting to rule the world. Griffin's dialogue includes some of the best-ever insane ranting, and thus we enjoy identifying with his spectacular aims. When, at the end, Griffin dies, his final scene with his beloved is quite moving. His last line of dialogue is the now-cliché, "I meddled in things that man must leave alone," and it is after his death and return to visibility that we get our only look at him. |

|

Turnabout is fair play as his manlike creations overwhelm Dr. Moreau in Island of Lost Souls. ©1933 Paramount Pictures. |

|

Dr. Moreau: Megalomania Unrestrained The other great figure, Dr. Moreau -- played by Charles Laughton in Island of Lost Souls (1933) -- is not so sympathetic. A few of his traits are godlike pride, sadism, schoolboy humor, bestial lust, and outright blasphemy. Parker, the protagonist of the tale, becomes stranded on Moreau's island and is at first disconcerted by the beast-like nature of the place's inhabitants. The only attractive one is Lota, a native woman whom Moreau has educated. Parker finds that the natives worship Moreau as a deity. Horrified, Parker confronts Moreau and is told and shown Moreau's secret: forced to flee England after one of his earlier experimental animals "ran shrieking into the streets," he set himself up on a remote island and, with a combination of techniques in his surgical theater (the "House of Pain"), transformed -- without use of anesthetic -- animals into quasi-humans. After showing his visitor one of his screaming experiments-in-progress, he exults, "Mr. Parker, do you know what it means to feel like God?" Parker promises to say nothing about what he has been shown if he is transported off the island. He flirts with Lota until, after he starts to make love to her, he finds his back scratched by her fingernails which have reverted to claws. Our "hero" is unable to countenance this, and angrily confronts Moreau. Moreau is not overly concerned for, having purposefully wrecked his own boat, knows that Parker is trapped on the island and will eventually be attracted to Lota once more. Who knows what sort of baby might result? Parker's fiancé learns of his whereabouts and, with the help of a ship captain, travels to the island. Moreau, upon seeing her, conceives new interspecies breeding plans, soon sending Ouran, a transformed great ape, to break into her room and rape her. The attempt is unsuccessful, but initiates the final events. After opposition from the captain, Moreau orders Ouran to kill him. The "ape" reminds him that this would be against the religious Law that Moreau himself has handed down to them. "It's all right tonight," mutters Moreau, and the beast-man does as bidden. The other "manimals " ask Ouran why he has broken the Law. "Law no more," he informs them. This, to their minds, gives them license to break the Law, and they capture Moreau, drag him into the House of Pain and, grabbing scalpels, subject him to the treatment he earlier gave them. Moreau is perhaps the quintessential mad scientist, and thus the movie has been dealt with at length. His work is as far beyond the pale as it is possible to go. The religion promulgated by him is so outrageous that Anton Szandor LaVey and his Church of Satan appropriated -- and enlarged upon -- its litany for use in their rituals, imputing to it an antiquity greater than that of H. G. Wells, who wrote the novel on which the movie is based.7 Unlike those scientists who have a basement full of "rejects," he, in his obsessive perseverance, has an entire island of them. He is, of course, ruthless when dealing with those who would bring him to the attention of the authorities. Moreau's demeanor is that of a tin-pot leader, a corrupt colonial administrator, who uses his exalted position for selfish purposes. And it is obvious that he enjoys being a god who can inflict continual suffering on his creations. It is this last detail that makes the film "unholy." Indeed, H. G. Wells's novel, an anti-vivisectionist tract that featured a less perverted Moreau, was written as "an exercise in youthful blasphemy."8 Many of the best films in the genre, including the "Frankenstein" movies, have echoed this. Blasphemy, however, has been the last thing on the minds of his present-day, real-life successors, whose genetic manipulations and interspecies breedings (including recent rumored attempts to mate humans and apes) have been efforts to "advance" science -- in an environment where "playing God" has become quite popular. A second remake of Island of Lost Souls, entitled, like the Wells original, The Island of Dr. Moreau (1996), takes account of these recent developments, but does not neglect the blasphemy elements, especially in the scene where Dr. Moreau, now played by Marlon Brando, arrives among his creations dressed like the Pope. An earlier remake in 1977, starring Burt Lancaster as Moreau, lacks this sort of lively madness. The Mad Scientist Transformed In The 1950s And 1960s Nineteen-forties practitioners continued primarily along the lines developed during the 1930s. The more imaginative evolution of the mad scientist in 1950s filmmaking is perhaps best expressed by Professor Morbius, played by Walter Pidgeon, in the science fiction classic Forbidden Planet. A man who has risked his life to obtain immense knowledge, by subjecting himself to an alien brain-boosting machine that has killed others, he has transcended normal humanity. But he has forgotten about his unconscious mind which, without his awareness, has been equally increased, creating a "Monster from the Id" which murders those who oppose him. It becomes evident that this had happened to the advanced beings who previously occupied Altair IV, the alien world where the movie is set, when planet-filling machineries for good became engines of ill will. When the Id Monster threatens Morbius's daughter, due to his unacknowledged incestuous feelings for her, he brings its fury upon himself instead. Before dying, he instructs his daughter's suitor to destroy Altair IV by using the planetary destruction system that is conveniently part of his lab's equipment. Despite the film's flaws, it provides glimpses of what super-genius might be like. |

|

Robur (Vincent Price), the inventor of a giant 19th Century airship, in Master of the World. ©1961 American International Pictures. |

|

One actor who played some mad scientists, but did not make a specialty of it, was Vincent Price. In one turn, as Dr. Warren Chapin, he shoots up LSD and experiments with a spine-cracking buglike monster in The Tingler, a gimmicky 1959 William Castle movie. While he often played tongue-in-cheek characters, one of his more serious ones was Robur, the inventor of a 19th century airship, in 1961's Master of the World. More typical of his ventures into mad scientist territory were his two turns each as Dr. Goldfoot (in the 1960s) and Dr. Phibes (in the 1970s), where his ingenuity was turned to preposterous uses. A far more realistic and disturbing scientist than any of Price's was depicted in the 1959 Georges Franju film Les Yeux Sans Visage (Eyes Without a Face), a French production that was released in the U.S. as The Horror Chamber of Dr. Faustus. Dr. Genessier, a ruthless plastic surgeon, had been responsible for his daughter's facial disfigurement in an auto accident. He dedicates his life to giving her a new face, a task requiring facial transplants -- which do not take for long. After her system rejects each one of them, Dr. Genessier arranges for the kidnapping of further unwilling donors. It soon becomes apparent that his motivation is not his daughter's happiness, but a desire to dominate. He is rebelling against a situation where he is made to feel less than godlike. The film is one of the masterpieces of the genre and the anti-vivisection message is effective. More Recent Mad Scientists Next we come to a film that was remade in the late 1980s: The Fly. The 1958 version produced two sequels. All concern the perils of teleportation (a word coined by Charles Fort), and obsessed scientists who try to perfect the process for the good of humanity, with "mixed" results. Care was taken to keep the first version from getting overly melodramatic, aiding believability. Indeed, its protagonist is so personable that one at no time feels that his doom is caused by his "presumption" at attempting the "impossible," making it one of the most fortean of the mad scientist films. The film's 1986 remake takes a refreshingly different approach to the story. The result is a kind of Love Story meets Lovecraft, and concerns scientist Seth Brundle's slow transformation into something "other" while he and his girlfriend try to cope with what this means to their relationship. The dialogue slyly mocks the clichés of the genre. The combination lab and living area that Brundle (Jeff Goldblum) uses is equipped with an upright piano for him to play in mad-scientist trademark style as he jokes to his soon-to-be girlfriend (Geena Davis) about how, now that she's seen what she's seen, he can't afford to let her leave. In the most famous mad scientist movies, only he and the aforementioned Morbius reveal to us that they have seen the classic horror movies featuring others of their kind. The writer and director of this film, David Cronenberg, operates on a higher level than most others who make this sort of movie. When Seth Brundle exults about the salvation humanity will receive from his invention, it is more than usually unnerving, since the characterization is crafted to resemble real born-again fanatics. Brundle soon realizes he is losing his humanity. Part of him is glad to be able to scientifically observe his changes into something beyond all previous limits. Yet he also regrets his losses. The present fear of transforming into something primal and unfeeling is also powerfully depicted in Altered States (1980) by screenwriter "Sidney Aaron" (Paddy Chayefsky) in the Ken Russell-directed film. The scientist in question here, Edward Jessup, is patterned after iconoclastic real-life scientists including John Lilly and possibly Timothy Leary. And this provides greater depth, for few "mad scientists" have been based on anything other than previous fictional personae, with the exception of Nikola Tesla, who was the model for several characters. Like his prototypes, Jessup is searching for the secrets of the universe, making use of psychoactive drugs to do so. By accident, his experimentations venture into territory where mind and matter join and he alters form, first to a rambunctious and destructive prehistoric man, and later into a primordial energy being. Eventually his love for his wife restores his consciousness to normal reality and he is able to regain the humanity he lost. He is far luckier than Dr. Jekyll in this regard. The element which has made these latter-day forays into the genre as good as they are is a more realistic attention to actual human concerns and ideas, reconnecting us with what was valid about them and their heresies in the first place, boding well for the continued vitality of the genre. Other "heresies" have sometimes been more colorful than realistic -- hence the films of Stuart Gordon, Sam Raimi, and others like them. In Gordon's 1985 flick The Re-Animator, adapted from H. P. Lovecraft stories, an enthusiastic young scientist named Herbert West (Jeffrey Combs) develops a method for reanimating the dead, which he uses with abandon. An enemy, Dr. Carl Hill (David Gale), after decapitation becomes one of the re-animated, making him even more formidable. Herbert West works for the sheer exhilaration of his quest, a facet which becomes even more extreme in the 1990 sequel, Bride of Re-Animator, directed by Brian Yuzna -- in which West tries combining assorted body parts of the living dead in unusual combinations, just to see what happens. A more innocent, if eventually ruthless, scientist on the edge is Peyton Westlake in the 1990 Sam Raimi production Darkman (1990). After the fashion of Preston Foster in Doctor X (1932), Westlake (Liam Neeson) has developed a synthetic flesh -- the only flaw of which is that it is temporary. He is mutilated in a subsequent explosion, and he uses the special flesh to disguise his hideousness when he seeks harsh justice against the criminals who scarred him in body and soul. Raimi's movie is not relevant to real-life "edge" scientists, but depicts one common aspect of the movie variety: their search for a personal justice. While mad scientists are a cliché, hence their increasing rarity in serious films, real "mad science" is in full swing as we enter the third millennium, and recalls the filmic versions of the 1930s and 1940s. Doctors can at long last transplant organs and limbs from one body to another with comparative ease. The basic programming of life is being mastered. Not only has genetic expertise produced modified lifeforms and clones, the code of the human genome has been cracked. Robots of all sorts have been manufactured, and ordinary folks have owned certain types as "pets." Machines the size of molecules have been created. Some of these even -- shades of Frankenstein -- combine biological and machine parts. In 2001, what once was heresy threatens to become normalcy.

Notes 1. Radu Florescu, In Search of Frankenstein (Boston: New York Graphic Society, 1975), pp. 226-227. 2. Ibid., pp. 78-79. 3. Ibid., pp. 81-87. 4. MagicImage Filmbooks Presents Son of Frankenstein: 50th Anniversary Edition (1939-1989), Philip J. Riley, ed. (Absecon, NJ: MagicImage Filmbooks, 1990), p. 59 (p. 9 of reproduced Willis Cooper screenplay). 5. John C. Lilly, The Scientist (New York: Bantam Books, 1981), pp. 171-172. 6. Philip Wylie, The Murderer Invisible (Rpt. of 1931 A.L. Burt., edition; Westport, Connecticut: Hyperion Press, 1976). 7. Anton Szandor LaVey, The Satanic Rituals (New York: Avon Books, 1972), pp. 83-105. 8. H.G. Wells, Seven Famous Novels by H.G. Wells (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1934), p. ix. The preceding article is a revision of "To a New World of Gods and Monsters: 'Mad' Scientists and the Movies," originally published in Strange Magazine #2, ©1988. |

|

|

|

|||